The concept that the present is the key to the past is called Uniformitarianism. The term means that the processes in evidence in the world today are assumed to have existed in the past, and a study of present events can be used to create models of past events. Uniformitarianism has become basic to scientific think- ing, and in the science of cosmology and geology in particular, it forms the cornerstone for modern concepts in geochronology. Before 1780, Uniformitarianism was not readily accepted. The dominant doctrine was Catastrophism. According to this view, the earth’s features and the fossil record for that matter, were the consequence of a series of global catastrophes, each of which had wrought extensive changes, both in the physical features of the earth and in all living things.

James Hutton (1726-1797) first championed the idea of slow gradual change to account for changes in the earth’s topography, but it was not until about 1830 that Charles Lyell (1797-1875), an Englishman sympathetic to the views of Hutton, documented uniformitarianism in his interpretation of the origin of the rocks and landforms of Western Europe. Lyell argued that the earth must be very old for its many geological changes to have taken place by such gradual processes. The presiding worldview of catastrophism

gradually gave way to uniformitarianism under the influence of scholars who adopted the views of Lyell. It is noteworthy, however, that many features of the earth’s topography are hard to explain by uniformitarian principles and so modern geologists have been forced to accept that rates of change may have varied considerably in the past, and catastrophic events have been employed more and more to explain some of the geological features of our planet. This swing in thinking even admits to short lived floods, storms and meteoric impacts as being possible agents of dramatic change. In the past few years geologists have thus come full circle, accepting the possibility that some of the catastrophic events in our geological past may have had more than local significance.3

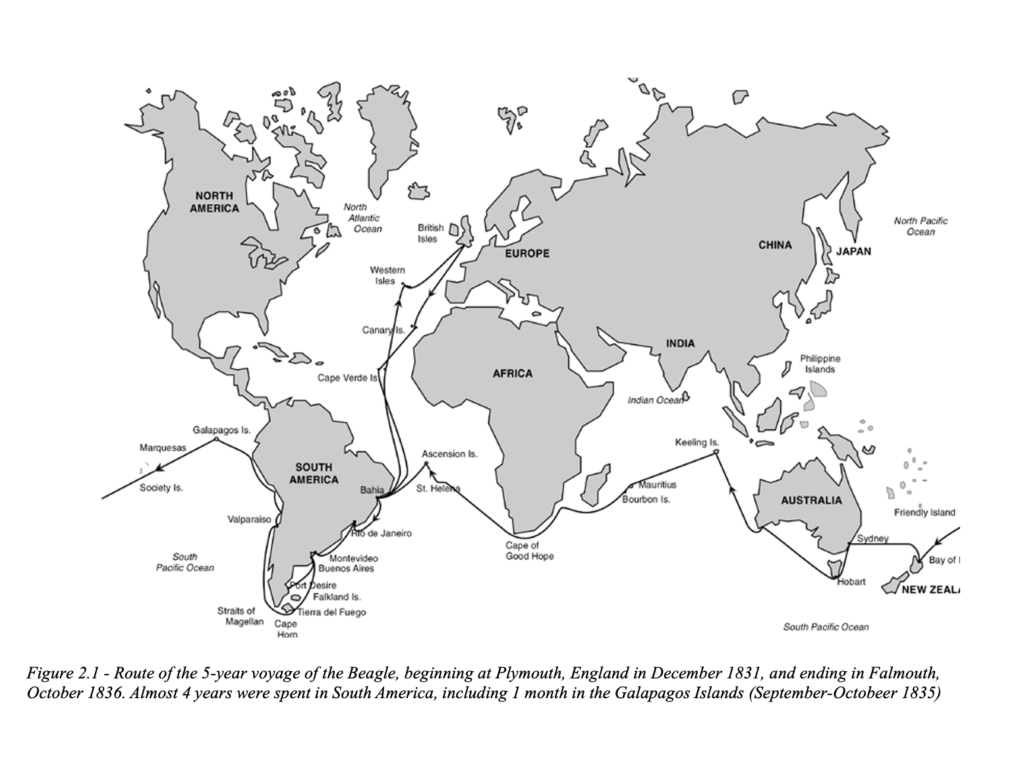

Charles Darwin was much influenced by the work of Lyell, and during the voyage of the Beagle, he carried with him Lyell’s Principles of Geology and assiduously noted the geological features of the many terrains he covered. The concepts of evolution were not entirely new to Charles Darwin, as his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802) had been an early popularizer of evolutionary ideas. Charles Darwin’s ideas on this issue only really crystallized during the voyage of the Beagle, and his experiences and observations on the lava-ridden Galapagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador probably had the most profound influence on his thinking. (See Figure 2.1) On these islands, he found the most unusual collection of organisms – giant tortoises and iguanas, many unusual plants, insects and reptiles and many varieties of finches. The finches, in particu- lar, interested him, as these normally seed-eating birds adopted the insect-eating habits of species such as warblers, which are absent on these islands. The subtle changes in form, structure, and habit of these birds entrenched the ideas of change over time and stirred the seed of evolutionary thought in Darwin, leading him to begin his first notebook on the Transmutation of Species in 1837.

It seemed reasonable to Darwin that the organisms on the islands had been transformed over time and that the new structures and habits had developed over time. However, the mechanism for the transformation of species was not nearly as easy to explain as the assumption that such transformation had indeed occurred. It must be noted that the world at that time had no knowledge of the science of genetics. Gregor Mendel (1822-1884), the father of genetics, was a contemporary of Darwin, but his work was unknown to the world at large and unavailable to Darwin.